Women’s career: does it make sense to base personnel development on “man/woman” criteria? Are common approaches to increasing the proportion of women in highly skilled jobs effective? And what about the gender quota?

It seems that hardly a day goes by when we don’t read the opinion of some male expert in the media who distinguishes the typical career behaviour of women in the workplace from the typical behaviour of “us men”.

Or from a female expert who begins her sentence by saying, “As we know, we women are …”, and then goes on to advise women on how to proceed in their careers.

When are generalisations useful?

Each of us has attitudes or behaviours that we judge to be right or wrong, good or bad. In addition, we are likely to surround ourselves with people who perceive reality through similar filters and confirm our views – birds of a feather flock together.

So, again and again, we observe other people behaving in ways that make no sense to us. Or others react strangely to our behaviour. This can easily lead to dissatisfaction and arguments. In such situations, we lack an explanation that puts the observation in a new, positive light.

Generalisations are useful for this purpose. Generalisations are descriptions of observable phenomena. Psychology has them, as do neuroscience, sociology and philosophy. With this common language, we can exchange ideas and gain new insights.

Through a new perspective, we may discover the bad in the good of our own habits, or the good in the bad of others’ habits.

Staff development: does the distinction between ‘man’ and ‘woman’ add value?

Would it be a stretch to say that (especially) baby boomer parents were more likely to tell their daughters “a girl doesn’t do that” or something similar?

No, this generalisation is not far-fetched. Such beliefs have been a barrier to pursuing specific careers and self-fulfilment for a significant number of women of the next generation. This knowledge can be very helpful in raising awareness amongst those affected, in sharing ideas with others, and in understanding typical symptoms and promising interventions.

However, this observed pattern does not describe the totality of women, but only a proportion of the total that someone considers significant! Regardless of how large this proportion is, in everyday life we are dealing with an individual and her individual life path: Ms Jane I-am-me. Ms I-am-me may or may not be a typical representative of the observed pattern:

- Can we know if Ms I-am-me’s parents behaved in the same way? No.

- Can we know whether Ms I-am-me reacted to her parents’ parenting methods with conformity or rebellion? No.

- Can we know if she is currently suffering from it, or has she long since recognised the problem and dealt with it (therapeutically)? No.

Women, Asians, Latins, migrants, the elderly, the handicapped, the highly gifted, the highly sensitive, … as useful as generalisations may be on a meta-level to describe phenomena, …

… any label attached to a person goes hand in hand with pigeonholing and an (unconscious) evaluation of the person, thus obscuring the view of a fair and unbiased perception of the person.

Increasing the proportion of women in highly skilled jobs

Let’s look at one phenomenon that can be observed regarding women in business.

Looking at the proportion of women in certain highly skilled occupations, as well as in leadership positions, reveals a serious imbalance. In Germany, for example, the share of women among STEM professionals – science, technology, engineering and mathematics – was only around 11% in 2019, according to Statista, while the share of women among STEM students was 29%!

How can we explain this observation and, more importantly, how can we achieve a more balanced outcome? The common thesis is that equal opportunity leads to equal outcome.

There are countries that have been making great efforts to make progress in this area for years – such as the Nordic countries.

And there are countries where gender equality is not a high priority – to put it mildly.

It stands to reason that the former countries have a higher proportion of women in STEM professions.

But no, this is not the case. A study by Leeds Beckett University, with the telling title “Gender Equality Paradox”, compared the Global Gender Gap Index of countries with the proportion of women among STEM graduates. The study shows that the former countries perform worse than the latter. The study also provides possible answers to explain this paradox.

Introduce a gender quota: yes or no?

Another pursued strategy is the “gender quota”, i.e., a gender-specific quota regulation for appointments to committees or positions. The hoped-for effect: positive role models “at the top” and thus a pull effect on the next generation.

Why not? I am always in favour of making a well-founded hypothesis on social issues and then testing it (with a pilot project). My fear is that this issue, like many others, will be approached dogmatically. Instead of testing the hypothesis and hoping to gain knowledge, the hypothesis could be treated as a “solution” set in stone and its maintenance defended to the hilt, even if the hypothesis is refuted.

The other related issue to keep in mind is illustrated by the following simplified calculation:

For the sake of illustration, let us assume that 100 STEM graduates are available for the labour market this year. Of these, 10% (10 people) have above-average talent for the labour market. These 10 are, of course, the ones that all employers want in order to secure a competitive advantage.

Let us further assume that the quota of women is 20% (20 women out of 100 graduates) and that the above distribution also applies to women. This results in the following: Among the 100 graduates, there are two women with above-average talent.

If you have 10 positions to fill this year and you have introduced a 50% quota for women, then you will voluntarily settle for three employees who are only of average talent!

Of course, only you can find out whether this generalisation applies to your particular case. To stay with this example: you may have a much larger pool of candidates, and you may be using a specific recruitment approach, so you have reason to believe that you will be able to attract five women with above-average talent.

A new perspective on the “man/woman” issue

In my view, generalisations are particularly relevant in practice when they provide us with a possible explanation for the motives and needs hidden behind the observable façade of the individual (m/f/d). Of course, these generalisations also have their limitations, as explained above.

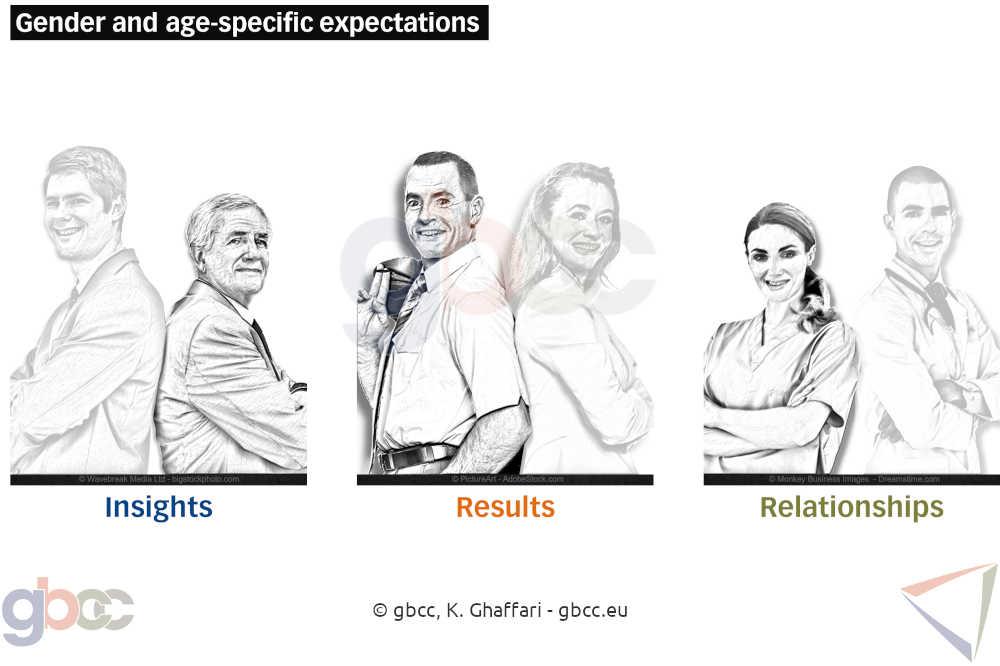

Personally, I think the model outlined below is quite relevant in practice. With this model you can also look at the issue of man/woman in a new way.

Let me start by briefly explaining the theory:

- We are dealing with three realities of life at the same time. You can think of it as a game played by three different rules at the same time.

- Each of us is exposed to the three rules of the game at all times, but each of us tends to favour one rule while neglecting another.

- The more relaxed we are, the easier it is for us to play by all three rules. The more stressed we are, the more likely we are to use our favourite rule.

In the end, we cannot avoid mastering all three rules of the game so well and routinely that we are always able to recognise the rules that are necessary to continue playing with confidence even under stress. These three realities of life are:

1. Achieving results

- What result do I want to achieve? What goals and milestones do I need? Who do I need? Who is going to take what first step to move forward?

2. Building relationships

- What are the needs of my counterpart? How can I recognise that my actions are good for me and for others? How can I build a good relationship with my counterpart – and with myself?

3. Striving for insights

- Do I know and respect my limits? Have I picked up the right lessons from my experiences? Do I have enough knowledge to answer the questions at hand? Have I sufficiently considered the opportunities and risks?

Advertising on my own behalf:

I refer you to my online courses if you are more interested in the rules of the game of these three realities of life.

Expectations of self and others based on society’s expectations

From a metaperspective, the pattern is that

- Japanese coexistence, for example, favours “Results”: the goal of the community seems to take precedence over the needs of the individual.

- The Italian attitude towards life, on the other hand, seems to favour “Relationships”.

- German social interaction, on the other hand, is conspicuously self-centred and favours dealing with problems (“Insights”) and criticising the actions of others.

Age and gender-specific expectations of oneself and others

From a metaperspective, the pattern that emerges – almost irrespective of culture – is that:

- Men are automatically assigned to ‘Results’ and the quality of their actions is judged according to the rules of the game there.

- Women are automatically assigned to “Relationships” and judged accordingly.

Another striking pattern:

- Useful knowledge and wisdom are automatically attributed to the elderly. And perhaps more so to men than to women?

The imprint of the individual (man, woman, Japanese, German, …) is ultimately the (largely unconscious) end result of all experiences of interaction with the environment. Each person deals with the expectations of others differently: some try to fulfil them, others rebel against them.

On the subject of gender expectations, thanks to the emancipation movement, women began to rebel against them many years ago, while men are probably only now beginning to do so.

How we deal with our dominant sphere and the expectations of others

If we are not aware of our strengths and weaknesses, our thoughts, feelings and actions will tend to be determined by others: I know:

- Men (specialising in “Insights”) who, as managers, gave the outward impression that they were at home in “Results” and felt perfectly at home there, when they were not.

Over the years, they trained themselves to have a doer’s attitude and a deep manly voice. They played it so well that for a while they believed it themselves, until a crisis of purpose hit them and they had to admit that they actually hated the doer attitude.

- Men (specialising in “Insights”) who become extremely irritable and thin-skinned when their private or professional environment expects them to “get their act together”.

Then they batten down the hatches and accept the consequences: a change of job or partner.

- Women (specialising in “Results”) who gave the outward impression that they were at home in “Relationships” and felt perfectly at home there, when they were not.

To the outside world, they appeared to be picture-perfect wives and mothers. “I have a wealthy and caring husband, healthy children, a beautiful home and my friends come to visit all the time. Why am I so unhappy? What is wrong with me?”

Until one day the realisation hit her: “Because I am (figuratively speaking) a Ferrari that professionally belongs in the fast lane of the motorway, but privately I drive on residential roads going 20mph”.

- Women (specialising in “Results”) who stand their ground as managers and become very irritable and thin-skinned when their private or professional environment expects them to be more “feminine”.

Then they batten down the hatches and accept the consequences: a change of job or partner.

These are just a few examples to illustrate the problem.

Interim conclusion:

- Leadership has traditionally been associated with the reality of “Achieving results”. Leaders, male or female, have traditionally followed the rules of this reality.

- In many organisations, today’s zeitgeist means that the primary focus of managers is on “Building relationships”. It is about identifying and meeting the needs of individuals.

Staff development and personal advancement

In all the discussions about quotas, personnel development, strengthening individual strengths, etc., it is easy to lose sight of this banal fact:

A company is made up of people who have joined forces in order to achieve results together.

This inevitably creates the “we” as the focus, and the individual (more or less) voluntarily subordinates their needs to the goals of the community. If doing this voluntarily seems unreasonable to me, it is a sure sign that I had better leave this community, for my own sake and for the sake of the community.

At the same time, everyone in the community would be well advised to pay attention to the individual needs of their own colleagues – procedurally and hierarchically. Everyone is well advised to help them to identify and live out their needs. Everyone would be well advised to help recognise their weaknesses and take them into account in the future. Why? Because their happiness or unhappiness affects the quality and quantity of their performance, which in turn affects our own quality and quantity.

At the same time, it would be sensible for each individual in the community to take care of themselves and their health, to know their limits, to respect them, to communicate them and to defend them. In short, I am well aware not to rely on others to take care of me.

Achieving results together requires a common mission

For individuals to decide whether they want to be part of the community and submit to it, the community needs a clear and attractive common cause that must be known to all.

This is a systemic problem. Many companies do not have a consensual mission, or have failed to communicate and implement it adequately. In many companies, different groups have different missions. Unproductive and costly conflict is therefore inevitable.

Only when the common mission is known and clear to all can we think about optimising the composition of the community: what should we look for in future recruitment of professional and managerial staff (m/f/NB)?

The answer depends, among other things, on which reality dominates! For companies, too, it is ultimately a question of balancing the three realities of life:

- Achieving results: e.g. profit generation and growth

- Building relationships: e.g. customer and employee satisfaction

- Striving for insights: e.g. risk management, financial data analysis. Questions such as “Can and should I afford this customer, this offer, this growth?”

Conclusion:

- Staff development in general, and women’s development in particular, is a complex system with many variables. The right path for your company will take into account all the variables that apply (only) to your company. What is your company’s solution?

- Most important tip: ignore easy recipes!

- Even if the initial situation is complex, the solution does not have to be: Let me run a two-day workshop with your top decision-makers, key people and/or multipliers, away from the daily work routine, and together we will develop a solution that fits your company.